See also previous Adrian Wilson Artist blog

New questions (from Geoff Davis, Micro Arts Group):

Q: You are well known as a graffiti artist (unsigned, online with the plannedalism tag) adjusting signs by changing or adding letters etc.

For you, is graffiti – (anti) literature, text art or social intervention?

A: My father and two older brothers were graphic designers and I have tried unsuccessfully to avoid graphic design my whole life. A couple of business students from Manchester University interviewed me in 1988 and in their synopsis stated that I had three business disadvantages:

I had no long term goals, was not motivated by money and in fact had refused to work for clients who weren’t anti-apartheid.

My graffiti is text based and definitely has a message. Even if I write a pun on a tree stump “I fought the saw and the saw won” it is to highlight the loss of the tree. Ideally my graffiti inspires people to think but doesn’t tell them what to think.

Q: Were you inspired by activist street artists like UK’s Banksy, or visual artists like Goldie?

A: I have always expressed myself one way or another from building snow sculptures with my kids, to over 30 years creating t-shirts (my first one in 1987, was a play on the Manchester A to Z street guide, changed to read “A to CRED”!), to the galleries I opened and the graffiti I am well known for, it’s all just been a fun hobby. Some people love kicking a ball, or playing an instrument but my brain is just wired to come up with visual ideas.

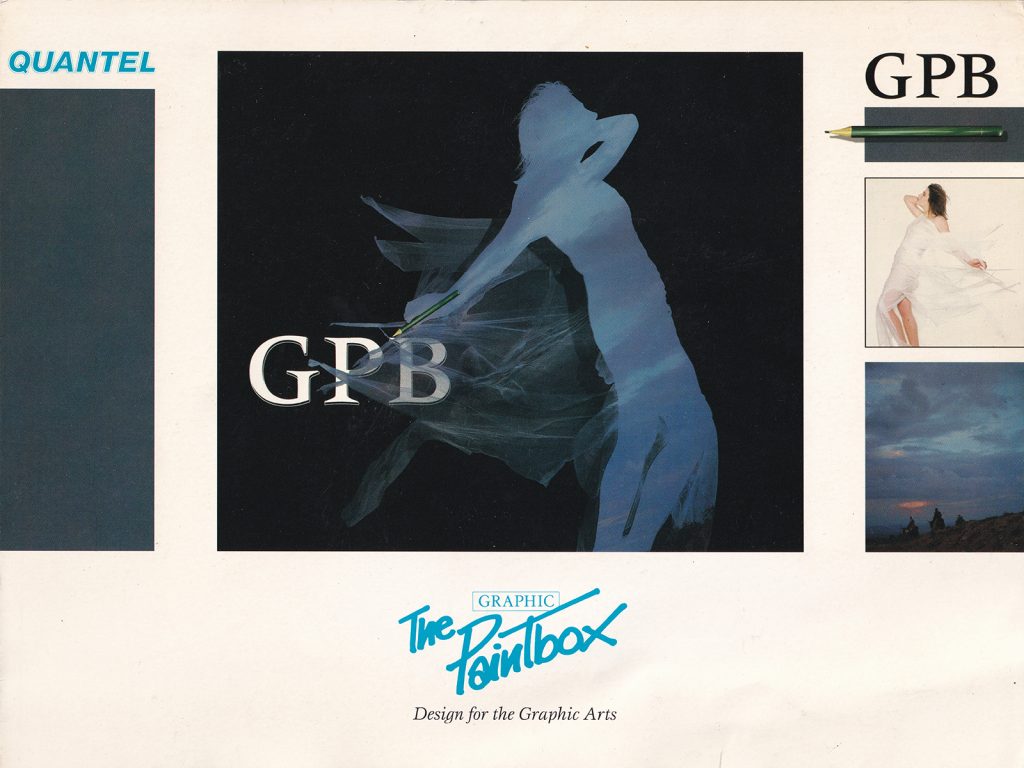

Q: Early Quantel – you mentioned, ‘make my ideas a reality with only a small amount of skill’.

Does this apply to the graffiti, and is that connected to fun, and using early Quantel Paintbox ?

A: Definitely. We all love to ridicule high brow art by stating “I could have done that” but to me, if someone sees a piece of street art I did and thinks “That’s something cool I could have done”, I have done my job well.

I have never taken myself seriously or set out to be referred to as an artist. I come from a northern family where my dad used to say “you’ve got to learn to stand on your own two knees”. That may have been a throw away pun but I always felt that lack of confidence or value in what I did. As the youngest of three males in the house, I was always referred to as “little Adrian” which probably drove me to be someone to do things to get attention, either a joke or something visual.

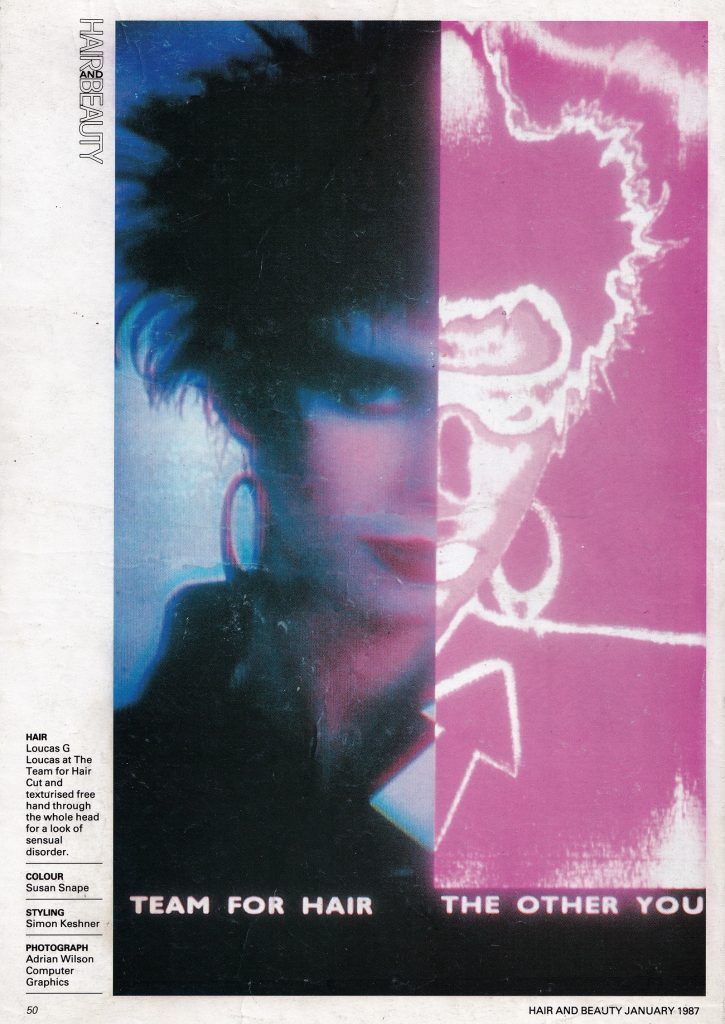

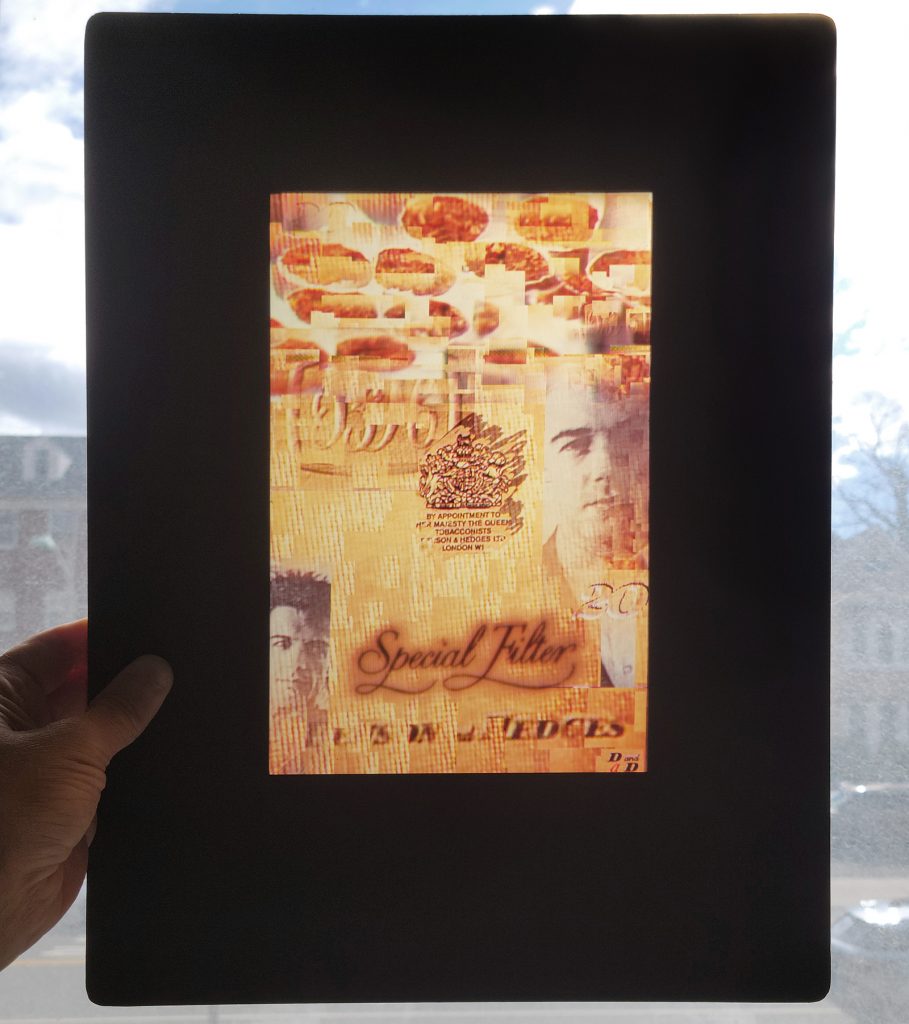

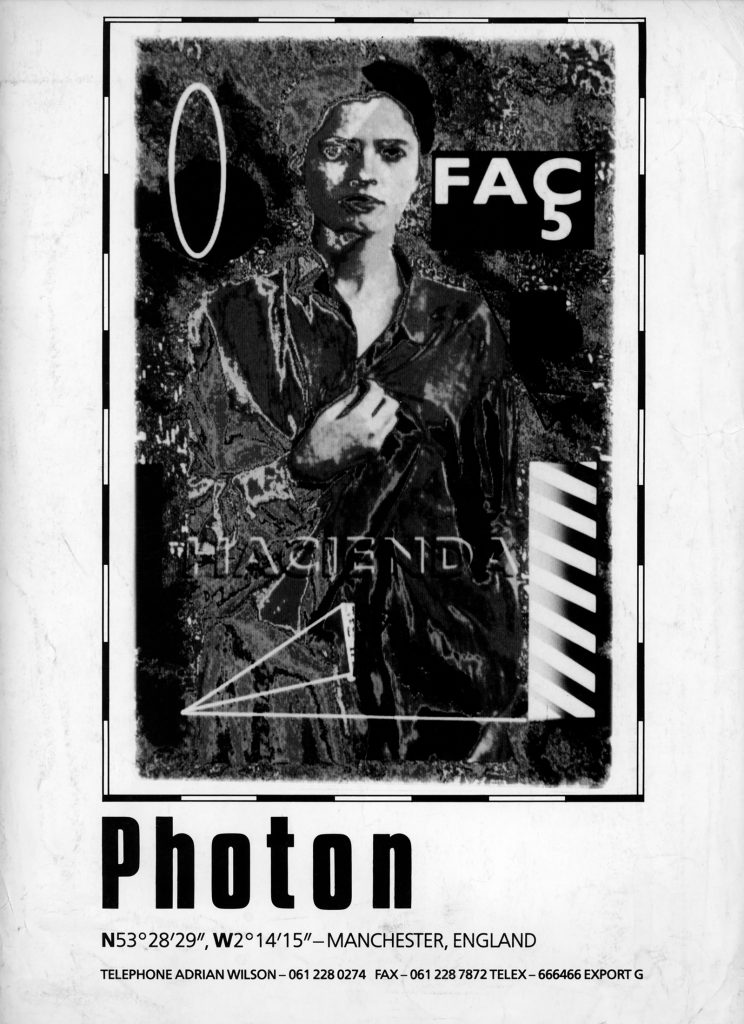

My Paintbox work was pretty dark but that was just the politics and aesthetics of the time. Anti-Thatcherism, The Young Ones and The Face magazine were my aesthetic, and I probably still relate more to Rik than Vivian in the way I interact with the world. Most of the jokes are for my own entertainment and if other people enjoy them, great and if they don’t, it’s fine too.

Q: How do you feel abut Photography vs painterly arts, on the work / labour / skill level?

A: There is a ranking in the “art world” in what is considered legitimate or superior, with oil painting at the top of the pyramid and photography closer to the base. As a photographer with 35 years’ experience, it is obviously second nature to me now and, thanks to digital, certainly easier than when I went to college.

Andreas Feininger was my biggest influence and he was all about scale and composition. Most of the photographic skills such as a knowledge of chemicals, lens behaviour or film types is about as useful as an A to Z Street Map nowadays. I think it is fantastic that a billion pictures a day are taken and uploaded somewhere because photography has always been about capturing a moment, whereas painting is about conveying an idea.

The biggest skill in photography and one for which it will be a long time before it is automated is a button which creates a good composition and that is really where the skill of a photographer is.

Lighting used to be important but not as much now with HDR, lateral range and photoshop. I have developed painting skills through practice but I can still only replicate something, not come up with new figurative ideas purely from my imagination. I greatly admire those who can paint and sculpt but in the same way I admire those who can sing or score a goal. There is no jealousy, just an appreciation for the different skills they have.

Q: Photography is famously technical, how does that connect for you with new digital outlets like NFTs, crypto art etc.?

A: It used to be technical but I am not sure I am even a photographer any more. Thanks to film and prints, my collection survived for 30 years in my mum’s attic and can still be enjoyed today. If I had stored my images on one of Quantel’s 8 inch floppies it would be unreadable, or the VHS would be fuzzy.

It saddens me to know that all I do now when I take a ‘photo’ is rearrange lots of 0s and 1s on an SD card. There is no definitive standard way it should look, in the way that when I scanned my Quantel slides I could look at a piece of film and try to match it. Of course we have social media and the cloud, so theoretically everything is stored for eternity but yes, because we all now accept something that doesn’t actually exist is a photograph, it is not too far a stretch to take a traditional certificate of authenticity and make a non existent version of that too.

Crypto is no different from touchless transactions such as Apple Pay as a method of digital transaction but the idea it is somehow safer or more democratic, is ridiculous. There is absolutely no link between the numbers and letters making up the blockchain ID to any individual, so if it is hacked, or stolen, or the company hosting your wallet stops paying for hosting fees, or you forget your login details, or there is a solar magnetic storm, you’re screwed. Once you provide ID and bank details to set up a digital wallet, it is linked to the same big banks and government tax department that your regular credit card is. History shows us that once something catches on and starts to make money, big business takes over and governments start regulating. Bitcoin is a digital casino and NFTs are digital tulip bulbs.

Q: Any new plans or ideas?

A: Honestly, like the business analysis said, I don’t plan that far ahead. Thankfully my kids are all grown up and I rent my apartment, so I haven’t got too many responsibilities and my health is good so at 58, I appreciate that fact more than any other.

My next big plan is actually graffiti within the digital world. I have some pieces in NY on roofs which are really only visible on Google Earth and the next plan is to use the lines of the crosswalks to create words and phrases that can only be read on Google Maps.

Taking it a step further, I have found a glitch in the system which enables me to change certain details of Google Maps, so I have few ideas up my sleeve. The old graffiti writers referred to painting the subway trains as ‘bomb the system’ and to me the oppressive ‘system’ now is not the city’s bureaucrats, it is the companies who control the digiverse and will be creating the metaverse. It will also be much cheaper than buying paint!

Q: How is NY after UK/London. An artist friend went to NY in 1996 and became a successful designer. He said it was safer/better than London. Any comments?

A: I stayed in Manchester rather than move to London to further my career and do love New York but it is just a bigger, expensive version of everywhere else. There are people who are successful because they are talented, or good looking, or well connected, or were at the right place at the right time. That is the same in Manchester or Manhattan. It is an honest city because it is just like the movies show it is – a giant money making machine full of people who didn’t fit in somewhere else, trying to survive in a place lacking in compassion for the individual. The good thing moving to NY is that one is expected to fail, so there is no shame in going back home after it has no further use for you. If you feel you want the challenge, try it but if you don’t, just visit for a holiday.

I can also lie in some Manchester nursing home bed and tell some nurse spoon feeding me rice pudding that “I once was famous for changing the names of the streets in the metaverse of New York” and she would pat me on the head, give me a sedative and say “Of course you did Mr Wilson”, then look on the metaverse and find it was true. Getting a twofer of free drugs and annoying a smart ass teenager is a near death goal of mine.

Q: Previously you mentioned NFTs of old work (could also be for new). Have you made any progress with this?

A: I sprayed “POST NO NFTS” , a twist on POST NO BILLS for fun and made an NFT of that. I also made an NFT of me deleting the video of the NFT the people made by burning a Banksy and another NFT of my friend the art critic Jerry Saltz, so you can see the angle I am taking. My next one will be a Schrödinger’s NFT, whereby I will either burn or frame a MAGA poster that someone gave me from Trump’s election night party in 2016.

Despite the flippancy and supposed dismissiveness, I do feel some gratitude to the concept of NFTs because without the hype, my Paintbox work would still be in my mum’s attic and I wouldn’t be the very proud and excited owner of a working Paintbox.

I met with one of the creators of cryptopunks and told him that I felt like he was like Mick Jagger, making a fortune commercializing and popularizing the work of unappreciated blues guitarists, with the side effect being that those guitarists become appreciated for being the originators. I feel that the NFT craze has been fantastic for the light it has also shone on the history of digital art, of which we should be proud to have played a part.

I have had approaches to sell my Paintbox work as NFTs but I haven’t found the right people yet. Ultimately, NFTs are like any other piece of art, they only have value if someone notable says why they are valuable. We are told that the Mona Lisa is the best piece of art in the world, so it is. Yet, we all know the shenanigans, hype and ultimately embarrassment of paying $450 million for the now discredited Salvator Mundi in the belief that it was a newly discovered Leonardo. Apparently the Beeple NFT that sold for $69 million has dropped in value by 75% but the person who bought it made a fortune because the purchase was his way of getting publicity for his cryptocurrency, which went up 2,000 percent because of the sale.

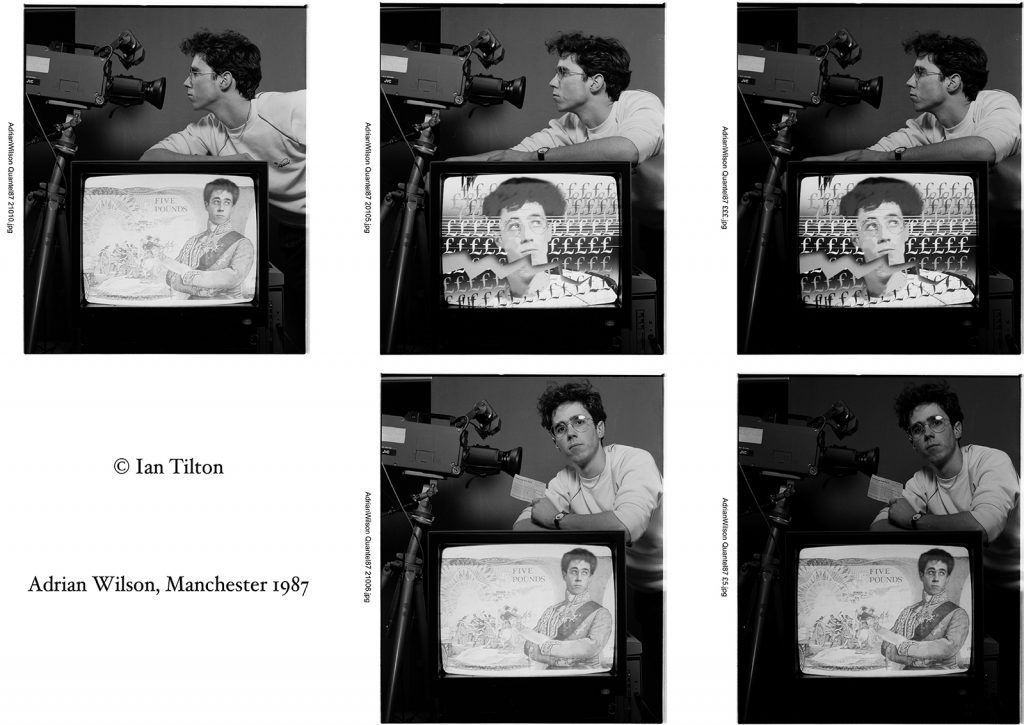

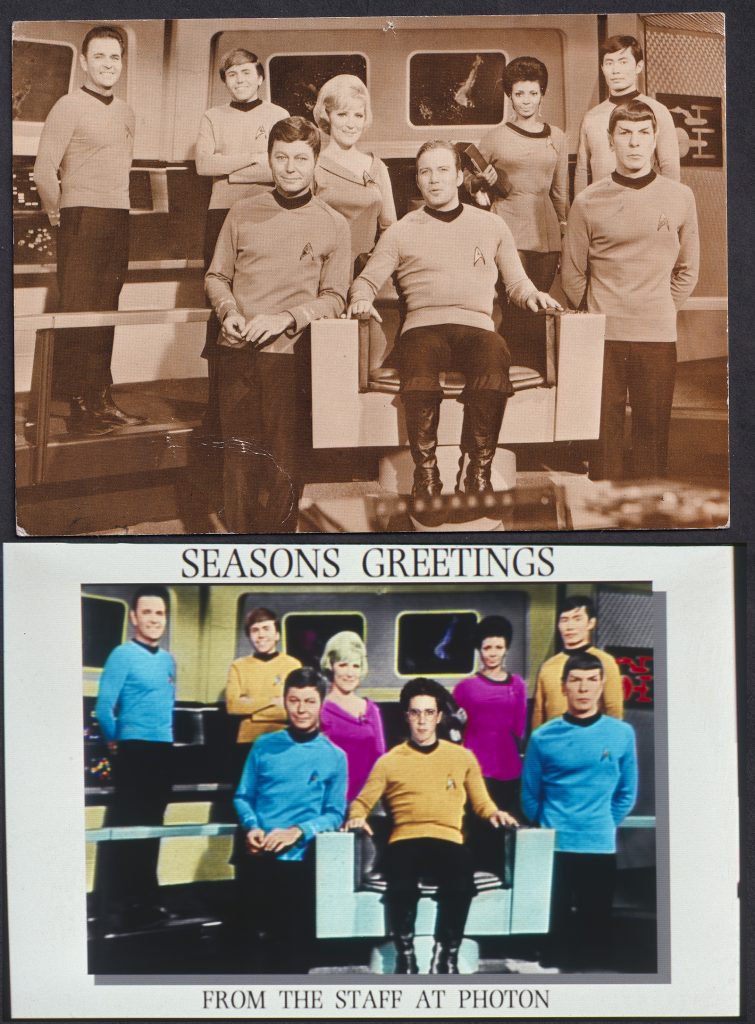

In theory, I created one of, if not the first digital meme when I swapped Captain Kirk’s head for mine on the Paintbox in 1987 and sent it out as a postcard with an ironic caption. With the right hype and people behind it, in theory, it could be worth millions. It’s just a funny postcard but once someone important realizes its place in history, it will become a valuable funny postcard.

I have been invited to put on a solo show at Blackpool School of Art’s art gallery from January 10th to February 18th 2022. To to me, that is the best full circle this story could have taken. I plan to take a Paintbox to the college to show the students what the Quantel people showed me 35 years ago. How cool is that?

Adrian Wilson November 2021

See also previous Adrian Wilson Artist blog

See (new page) NY.com article and interview about the graffiti – plandalism